For all people who aspire to create art – be it in poetry, fiction, illustration, textile design, photography, film-making – one of the biggest impediments to success is self belief (or lack thereof). With the various creative industries stretched and diminished by cuts to public sector arts funding, generally diminished budgets as print media declines, and an unwillingness of the major publishing houses, art galleries and film studios to gamble on unproven talent in favour of established artists – the challenges facing aspiring creatives are vast.

Such are the obstacles in their way, in fact, that it can be easy to become despondent and discouraged – falling into a general malaise that can ultimately prove fatal to the creative impulses necessary to make new and interesting art.

But, of course, this is not necessarily a new phenomenon (although our modern digital world does have its own unique factors that can prove disruptive to creativity). Indeed, artists have been struggling with feelings of self-worth and personal belief in their work for centuries. In Nichomachen Ethics, for instance, Aristotle discusses at length the vital importance of what we might essentially call self-confidence.

Even artistic titans are far from immune from such feelings – or such lack of confidence in themselves.

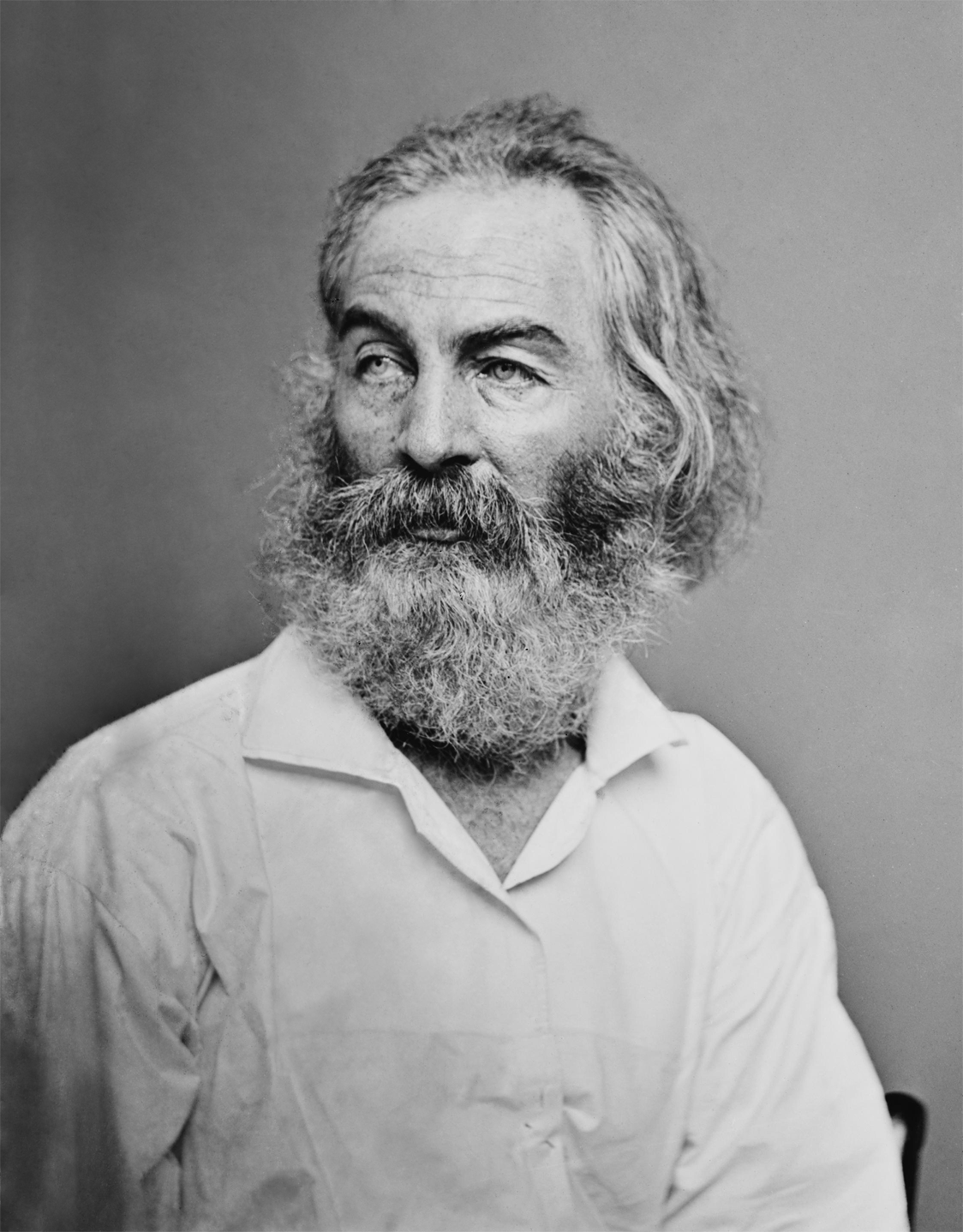

On July 4, 1855, Walt Whitman self-published Leaves of Grass — the monumental tome, inspired by an 1844 essay by Ralph Waldo Emerson titled The Poet, that would one day establish him as America’s greatest poet. But despite Whitman’s massive expectations for the book, sales were paltry and the few reviews that rolled in were unfavourable.

Whitman, who had been supremely confident the book would do well, soon faced a crisis of confidence when his work failed to take off. This is perhaps not surprising, considering some of the reviews he received.

Writing in The Atlantic, Thomas Wentworth Higginson said of Whitman’s book: “It is no discredit to Walt Whitman that he wrote Leaves of Grass, only that he did not burn it afterwards.”

Rufus Wilmot Griswold , the literary critic for The Criterion, meanwhile, dismissed Leaves of Grass simply as “A mass of stupid filth”.

In the face of these reviews, Whitman felt compelled to supply his own (incredibly positive) review of his work to countenance them. He submitted an anonymous review of Leaves of Grass to The United States Review, in which he claims his poetry “brings hope and prophecy to young and old”, and explains that “Every word that falls from his mouth shows silent disdain and defiance of the old theories and forms. Every phrase announces new laws; not once do his lips unclose except in conformity with them.”

That Whitman was driven to write such glowing self-praise is evidence of a deep insecurity that his work was not becoming the success he expected it do be.

Yet Whitman was saved from falling into a soul-searching pit of remorse and self-disbelief by an extraordinary letter of praise from none other than Emerson himself, who was not only the muse for the volume but also, by that point, America’s most significant literary tastemaker. The missive, found in the formidable but enchanting volume The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson (public library), is nothing short of spectacular — both in its beauty of language and its generosity of spirit:

“Dear Sir,

I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of Leaves of Grass. I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed. I am very happy in reading it, as great power makes us happy. It meets the demand I am always making of what seemed the sterile & stingy Nature, as if too much handiwork, or too much lymph in the temperament, were making our Western wits fat and mean. I give you joy of your free and brave thought. I have great joy in it. I find incomparable things said incomparably well, as they must be. I find the courage of treatment which so delights us, & which large perception only can inspire.

I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start. I rubbed my eyes a little, to see if this sunbeam were no illusion; but the solid sense of the book is a sober certainty. It has the best merits, namely, of fortifying & encouraging.

I did not know until I, last night, saw the book advertised in a newspaper, that I could trust the name real & available for a post-office. I wish to see my benefactor, & have felt much like striking my tasks, & visiting New York to pay my respects.

R.W. Emerson”

There is something particularly magical and generous about an established cultural icon taking a moment to send a note of appreciation to an emerging talent who one day becomes a celebrated icon in turn.

It is, of course, often easier to be a critic than a celebrator. But Emerson’s letter proves the real value of the gift of appreciation – and of support for a fellow creative. After all, we could all use a little recognition and encouragement.

Leave a comment