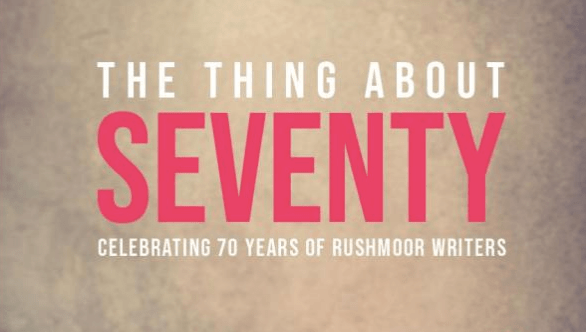

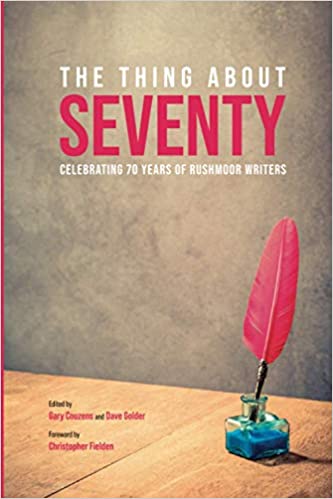

On November 1st 2020, Rushmoor Writers turned seventy years old. It’s the second-oldest writers’ group in the UK, after the Authors’ Club, which was founded in 1891. To celebrate this milestone, the writers group has published an anthology of new writing, The Thing About Seventy.

The anthology features tales of love, loss, lockdown, dragons, abandoned houses, dead people, mystical crystals, rebellions in the supermarket and vanishing numbers. And in all, there’s a thing about seventy. It’s available from Amazon as a paperback (£7.99) and as an ebook (£2.99). Here at NITRB, we’re incredibly pleased to bring you the following exclusive excerpts from the book.

What Happened To 70?

C.R. Berry

Amy Sakamoto pulled into the car park of the Fairview Hotel, still reeling and shaking and wanting to punch things. No, it wasn’t fair that she was here. Jeff was the one who’d been fucking someone else. But when he’d admitted to having that slut-whore in their house, in their bed, she just couldn’t be there anymore. She had to get away and be alone somewhere. Throw herself into the piece she was writing for her column in The Overlook and try and forget all about that utter shithead.

Easier said than done, of course. Once in her hotel room, Amy sat down at a tiny desk with her notepad and pen and a cup of tea, but the ink wouldn’t flow. She kept imagining Jeff screwing Delilah, a mutual friend who was actually more Amy’s than Jeff’s. Well, used to be. Now she could go fuck herself in the eye.

Amy gave up. She’d try again in the morning. She went into a bathroom that was so narrow her legs grazed the wall when she sat on the loo, and poured cold tea down a sink big enough to wash one hand. Then she attacked the minibar with guilt-free fervour. She poured herself a gin and tonic that was almost half and half, before heading out of her room to get ice.

That’s odd.

She was walking down a corridor with rooms on both sides.

Room 68. Room 69. Room 71. Room 72.

Where was room 70?

She went back along the corridor, just in case she’d missed it.

Most odd. The hotel was missing a room! Perhaps there was some superstition here about a room 70, just like many hotels didn’t have a room 13. Returning to her room with ice, Amy wondered what dreadful things might’ve happened here in room 70 for the owners to pretend it didn’t exist.

The next day, she checked out having written a grand total of fourteen words for her article. She said to the receptionist as she handed in her key, ‘So what’s the deal with room 70?’

‘I’m sorry?’ said the receptionist.

‘I noticed you don’t have a room 70. Is there a story there?’ Hopefully her journalistic curiosity wasn’t too obvious.

‘What do you mean, a room 70?’

Amy frowned. Am I not speaking English?

‘Your rooms go from 69 to 71.’

The receptionist arched one eyebrow. ‘Yes.’ Her expression added, And?

‘Well, I was just wondering what happened to 70?’

‘I’m sorry, Miss Sakamoto, I’m afraid I don’t understand the question.’

Dumb as a bag of hammers. Amy walked out with her travel bag.

Even though Jeff would be at work, she’d planned to put off going home for as long as she could. It was her dad’s birthday today—the big 71. She wasn’t scheduled to see him till the party at the weekend, but decided to go see him today anyway. She just needed to pop to the shops and grab a card.

Something occurred to her as she looked at all the 71st birthday cards in Woolworths. Why was 71 such a big milestone? Why not 70? She looked at the cards for 60th, 50th, 40th and 30th birthdays. 70 was conspicuously absent.

Then it dawned on her. She was wrong. Her dad wasn’t 71 today. He was 69 last year, which made him 70.

Wait—is that right? He was born in 1914, so yes, that was right. 1914 was 70 years ago.

But there weren’t any 70th birthday cards.

Amy asked the shopkeeper, a grouchy-looking man in dire need of a razor. He frowned at her. ‘70th? I don’t understand what you mean.’

Amy shook her head. Seriously, have I lapsed into Japanese? ‘Forget it.’

She bought a ‘Dad’ card instead, and left.

Hardcastle’s Dragon

Martin Owton

Squire Hardcastle tethered his horse to the post beside the horse trough at the corner of the marketplace and paused to brush the dust off his coat.

‘Mind him for us, lad.’ He tossed a farthing to a cross-eyed boy who sat nearby and set off up a side street of handsome stone houses. He stopped at a doorway and peered suspiciously at the small brass plate on the wall; it read Office of the College of Wizards. He tugged on the bell pull beside the plate and waited. Presently the door opened and an elderly woman conducted him inside.

The interior smelt pleasantly of lavender and the beeswax polish that had evidently been lavished on the wall panelling and floorboards of the corridor. Squire Hardcastle could feel the maid’s disapproval boring into the back of his head as his hobnailed boots scuffed across the floor. The corridor ended at a door that was equally as well polished. He knocked gently on it just below the plate that read J Hoskins, Clerk to the Wizards.

‘Enter,’ came a voice from beyond the door. Squire Hardcastle did as he was bidden.

J Hoskins sat behind a large wooden desk with an ornate inkstand, and a second plate reminding the world that he was Clerk to the Wizards, placed between him and his visitor. He was a small man with a large nose whose hair had retreated to leave grey tufts at the side of his head as if a dormouse perched over either ear.

‘How may I help you?’

‘I’ve got a dragon,’ said Hardcastle, looking around for somewhere to sit down; there was nowhere, save the rug.

‘You mean it belongs to you?’ said Hoskins.

‘No,’ said the Squire, his broad vowels rolling round the room. ‘I mean it’s on my land, eating my sheep and summat needs to be done now.’ Hardcastle stopped just short of banging a meaty fist on the desk.

‘And what do you want done about it?’ asked Hoskins mildly, making a bridge of his long pale fingers.

‘I want rid of it, soon as you can. It’s costing me a fortune. Seventy sheep it’s eaten.’

‘Ah, right.’ Hoskins pulled open a drawer of his desk and extracted a sheaf of papers. ‘You’ll need to fill these in then.’

‘What’s this lot?’

‘There’s a registration form and there’s the proposal form. You’ll need three copies of the proposal plus any supporting documentation.’

‘Proposal?’ Hardcastle’s brow furrowed. ‘What proposal?’

‘The proposal of action against this dragon of yours. We can’t just send in a wizard without a full plan of action including timelines and contingencies.’ Hoskins looked pityingly at the Squire, his eyes like two boiled gooseberries. ‘Wizards are incredibly busy people. There are far too many requests for assistance for all to be fulfilled, so they have to be considered by the committee and, if approved, appropriate resources will be allocated.’

‘How long does that take?’ The furrows deepened.

‘Oh, not long. It’s quite efficient,’ said Hoskins with a smile. ‘When you submit your proposal it will go to the appropriate subcommittee, and they’ll pass it to the full committee, if they approve it. The subcommittees sit every four weeks and the full committee every six weeks.’

Seventy Pieces of Glass

Jane Sleight

On the day of their lunch date, Caroline got up early and tried to make herself feel attractive. By no stretch of her imagination was she beautiful, she knew, but she tried to look after herself and apply make-up befitting a forty-four-year-old dressmaker. She still called herself that, though she rarely made dresses now. A one-off request to make a bespoke veil and beaded headpiece for her cousin’s wedding fifteen years back had propelled her into the crazy world of weddings and now she had more than enough work to keep her busy and living in comfort. She’d been lucky enough to inherit her parents’ property at a boom time in the market so had invested the profit from the sale in a top-floor apartment with picture windows and a sea view.

She had booked a table at her favourite restaurant. She didn’t know what Ben liked, but it catered for meat-lovers as well as vegans and was the top-rated place in the area. She loved to eat out and never felt alone at her table for one, always taking a book with her to escape the stares of other diners. She strolled from her apartment along the seafront, through Regency Square and past the mosque to her destination.

The owner of the restaurant greeted her warmly. ‘Hallo, Miss Caroline, lovely to see you. No book today, not when you have a handsome companion, eh? I’ve taken him to your usual table.’

She’d expected him to be late, or not turn up at all, and a bolt of excitement flashed through her, like a static shock. She would finally get to meet him. Shake his hand. Hear his voice in person and stare into those beautiful eyes. She followed the waiter and saw the back of Ben’s head. There were touches of grey in his closely-cropped hair, which pleased her, though she didn’t know quite why.

‘Hallo, Ben.’ She watched as he got up and turned to face her.

‘Caro! Bloody lovely to meet you, after all these years.’ He bent down and gave her an enveloping hug with his six-foot frame and muscular arms. She breathed in his musky aftershave.

‘You too.’ She sat down and looked at him properly for the first time. She hadn’t seen a picture of him for years. The eyes were the same sparkling blue ones from his youth, but his face was scarred quite badly. He had a short beard, just stubble really, but multiple scar lines marked his face and gave him a slightly menacing appearance, though it wasn’t frightening to her. She felt a wave of pity towards him.

‘You look lovely, Caro.’ His voice was deeper than she remembered from their rare phone calls.

‘Thank you. What would you like to drink?’

He flinched. ‘I’m fine with water, thanks.’

‘Me too.’

He poured her some from the jug on the table and she held up her glass to toast him.

‘Welcome to Pommie Land.’

He nudged his glass against hers. ‘Thank you.’

A waiter handed out menus.

‘So, tell all. What have you been doing since you landed?’

‘Aargh, I’m exhausted. Spent a week in London, doing every tourist thing ever invented. Went to Woking to see Auntie Mary and her lot for a few days. They dragged me round more rellys than I knew existed. Thought I was gonna die of tea poisoning. Then I made my way down here.’

‘You didn’t say how long you were going to be around for. Is it just lunch? Or can you stay a bit longer?’

‘I’m due back at Heathrow in eight days. Got no plans yet. Thought I’d pick your brains about what to do. You know me better than most.’

She frowned. ‘Do I?’

‘Well, you’ve known me a long time. Before…well, doesn’t matter. But yeah, I reckon you know me pretty damn well.’

‘It’s thirty years isn’t it, this month. Since we first wrote.’ She smiled. ‘Where are you staying tonight?’

‘Not decided.’ He locked his gaze onto hers. ‘Where do you recommend?’

‘Well, Hotel Caro’s the best place round here.’ She let out a nervous giggle.

He laughed. ‘And does it have guest rooms?’

‘Only one. But you’d be very welcome to it. I assume it’s…just you?’

‘Just me. That’d be great. Give us a chance to catch up properly.’ He gave her the broad smile she knew well from photos in the early years. The scarring on his face didn’t diminish its beauty when he smiled.

Caro was relieved when Ben ordered a steak. She was sure the non-meat options were good but had never tried them. Her love of red meat hadn’t waned since her first trip to a Beefeater steakhouse in the Eighties with her parents. It seemed odd that he hadn’t organised somewhere to stay but maybe he hadn’t wanted to presume she would put him up. And men didn’t do detail, in her experience. Certainly, Josh never had.

He gave her a piercing stare. ‘Why did you come off Facebook?’

She pondered while returning his gaze. ‘Let’s just call it divorce fallout.’

‘You didn’t want the divorce, did you?’

She shook her head.

‘But you’re OK?’

‘Yeah. Now. What about you?’

‘Physically, I’m as healed as I’ll ever be. The rest is a work in progress.’

The waiter brought their starters. She’d chosen her favourite hummus and pitta and the smell of the garlicky dip and the chargrilled bread made her salivate. Ben had gone for the mussels that were cooked in a fennel and tomato sauce. The aniseed aroma reminded her of trips to the sweet shop as a child.

She offered him some bread. ‘I won’t ask what caused the injuries. I’m guessing it’s not a convo for a public place.’

‘Ha-ha, convo, we’ll turn you into an Aussie yet. But yeah, not for discussion now.’

Three Times Seventy

Jennifer Riddalls

Painted Departures

The girl from Rainbow Wishes paints Nell’s face, sweeping the sponge and flicking the brush. After, my daughter looks at her reflection and my heart stutters. It’s the first time she’s been able to look at herself and smile for months. I realise I won’t be able to kiss her, or I’ll smudge the paint. I pat the nylon wig and as she slips away, I kiss her hand instead.

Walking in Someone Else’s Shoes

Helen Matthews

The man must have lied about his age but it’s too late now. He’s shaken hands with Manee’s father and paid for a plot of land with almost a sea view where her parents will build their dream home. Her family’s problems, accumulated like sludge in a sewer over the past four years, have been scrubbed away with the stroke of a pen on the marriage certificate. In the photographs of the ceremony everyone is smiling broadly. Everyone, except Manee.

Before agreeing to let her father sign her up with the marriage agency, Manee talked it over with her cousin. Her cousin’s friend’s sister’s daughter had been mail-ordered by an Englishman through the same bridal agency and now lived in a place called Darlington in the north of England.

‘What’s it like there?’ Manee asked her cousin.

‘The sky is grey like funeral ash and it’s always cold,’ said the cousin, ‘but she say her husband let her keep central heating on all through summer because he feel cold too.’

‘And what’s her best advice?’

‘Her advice is – think about the man’s age. Choose wisely.’

Manee nodded, anxiously. Ever since her father yanked her out of her studies because of their family’s financial crisis, she’d been constantly anxious and huddled indoors under a blanket of depression. She’d been studying Pharmacy at the university and, on the day she was told to leave, she went to the library and stole three hefty textbooks, thinking to continue her studies independently. She sat in her room, which wasn’t even a room, just a shack in the garden at her aunt’s place because her parents had sold their home to pay debts, and stared at a Chemistry text book while a grey mist floated in front of her eyes and blotted out the words.

Four days before the wedding, Manee was introduced to her husband-to-be. She was appalled. He had thick silvery hair, a suntan, a nice smile and all his own teeth. Where was the leathery wrinkled skin, the folds of lizard flesh under his jawline?

‘I’m seventy,’ the man told her proudly, ‘but my friends say I don’t look a day over sixty-two.’

‘Only seventy!’ Manee gulped, remembering her cousin’s advice about age. She’d told her father to tick the box for a fiancé aged eighty-five plus but he must have ignored her. This man looked as if he might live for years, even decades…

And then it would be too late to achieve her ambition to become a pharmacist.

In their honeymoon suite at the best hotel in Pattaya, the man tells her about the plans he’s made with an agency to do the paperwork to get Manee a UK Settlement visa.

‘Don’t worry, honey,’ he says. ‘You’ll easily pass the English proficiency test. Your university course was taught in English, wasn’t it?’

Manee nods.

‘Legal marriage in Thailand is recognised in the UK so you’ll get a visa valid for two years and nine months. After that we can apply for another one to take you up to five years.’

Manee’s heart beats faster as she sees her youth and her dreams ticking away. Five years from now, ten years, this man will still be fit and active. But what happens after fifteen years? She won’t be a pharmacist, she won’t even be a nurse, she’ll be a carer.

‘Why is the visa for two point seven five years?’ she asks.

‘To prove to the authorities our marriage is genuine, my love. It is for me. I adore you already.’ He looks solemn, almost sad, as he bends to kiss her but he reeks of whisky. Manee’s father kept refilling his glass. ‘Come here my dearest darling.’ He holds out his arms to her, overbalances and collapses onto the bed.

Manee takes a few steps away.

‘Where are you going?’ he asks.

Shyly she nods towards the bathroom door. ‘There.’

‘I’ll wait.’

In the bathroom, she peels off her wedding dress and drops it on the floor where it deflates like a soggy meringue. Manee wanted to wear traditional Thai dress but her mother had insisted on wrapping the goods ‘western-style’. She runs a shower and waits.

By the time Manee tiptoes out, the man is fast asleep and snoring.

While they wait for Manee’s visa paperwork, they move to a rented apartment in Bangkok. She knows the man’s name is Stuart and her mother has drummed into her that her role as a wife is to serve him and make sure he keeps on sending money to build the family’s new house on the recently-purchased plot.

At the market she buys chicken and coconut, fresh lime and rice. She hesitates over the fruit called durian. It tastes divine but gives off a stench of tobacco and sulphur. Every evening Stuart eats the meal she cooks, thanks her and drinks moderately until ten o’ clock. Then he wants to make love to her but he can’t seem to manage. He whispers, ‘Sorry,’ and promises he’ll get it sorted out when they’re back in England.

After he falls asleep, Manee gets out her Pharmacy text book and looks up his condition. The name of the drug to treat it begins with ‘v’ – a word she can’t pronounce. She’ll make sure he doesn’t get it. Their lacklustre love life suits her.

Seventy Memories of the 1970s

Dean Hollands

I was born in 1966. When the next decade started, I was four years old; by the end of it I was fourteen. I grew up in an iconic decade that shaped a generation: my generation, the last preelectronic generation.

I am a child of the Seventies, a decade that started in black and white and ended in colour. A decade in which – politically, economically, socially, technologically, legally, and environmentally – so much was wrong with society in Britain. Yet, so much was so right. Submitted for your consideration are seventy of my memories, good, bad, and indifferent, in no order, no priority and no preference. I am a child of the Seventies.

70. Adults could beat you up and routinely did

Parents, neighbours, policemen, shopkeepers (especially if they caught you nicking). Violence against kids I recall was actively encouraged. Had it been an Olympic event, Britain would have dominated for decades. It was rampant, and something of a national pastime, until Esther Rantzen and her bloody Childline telephone support services came along. Suddenly adults stopped openly battering kids for no good reason, and apparently just being a pain in the arse ceased to be a good reason. In reality, I still got more than my fair share of private whacks, kicks and thumps, and suspect I was not alone. I guess kids like me, cocky, confident and a tad arrogant, were our own worst enemies, whether it was unbridled bravery, or sheer naivety, but I once threatened my father with calling Childline. In return for my spontaneous act of audacity, I received a blooming good slap for my trouble and needless to say never made the call.

69. School bullies

Not kids, but teachers. They were the worst kind. Head cuffing and ear boxing for no fathomable reason were routine, often with an open hand but occasionally a book was deployed. Educational enlightenment was reinforced by way of a wellplaced headshot from a blackboard rubber; a direct hit would gain the teacher serious staffroom bragging rights. It was also okay to detain you at lunchtimes and after school almost indefinitely without your parents’ permission or knowledge. I had one teacher who delighted in allowing you to exchange your detention for a punch in the stomach.

68. Corporal punishment

No, not Dad’s Army. I’m referring to ‘Attitude Adjustment Therapy’. A visit to the head’s office for a good old-fashioned caning gained you instant hero status throughout the school. Sometimes, just for a laugh, I would sit outside the head’s office just long enough to be seen and for a rumour to start that I was waiting to be caned. I naturally confirmed such rumours, declining to show my welts, having opted to have my arse caned, which I couldn’t possibly show, unlike the welts on the palm of my hand that I wore as a badge of honour for all to see.

67. Keeping up with the Joneses

My mother was always ordering the latest must-have home convenience item from her Kays home shopping catalogue. Hostess trolley, teasmade, SodaStream, fondue set, pressure cooker…we had the lot.

66. Fun was created, not bought

Ring pulls were sharper than razor blades and you fired them at your mates. Paper wads fired from elastic bands wound around your forefinger and thumb could take an eye out, but you did it anyway.

65. Put a tiger in your tank

All forms of transport pumped out insane levels of lead and other carcinogenic chemicals, but our parents still encouraged, nay insisted, we played outside. Factory chimneys weren’t much better, bellowing huge toxic plumes of smoke, but that was okay – they looked nice against the grey sky.

64. Clunk click, every trip

Most people never wore seatbelts. It wasn’t compulsory, so why would you? Kids sat in the front and sometimes on dad’s lap while you steered the car and he controlled the pedals.

63. Kids were seen and not heard

As a kid I couldn’t go into a pub, but I could sit in the car, in the pub car park, while Dad fetched me out a packet of crisps and a can of Coke. I wasn’t allowed out of the car and time was spent trying to communicate with the other kids in the other cars and convincing my brother it was safe to stick his finger in the cigarette lighter. Which he always did.

62. Smoking can damage your health

That was the government warning emblazoned on every packet of cigarettes from 1971. Despite which, people smoked everywhere and anywhere. In cinemas and restaurants, sections became non-smoking (genius) but that didn’t stop the smoke drifting into the non-smoking sections. Mum and Dad smoked indoors, that was normal, and during car journeys I was trapped in the car with my parents merrily chain smoking their way to an early death, the windows wound up so they could hear the radio better, immersing me in a fog of carcinogens that made my clothes stink of fags, too.

61. Playgrounds were fun

Dangerous, but fun, with every chance a hot metal slide would scald you, or you’d cut yourself and contract tetanus, but that’s what memories are made of. Playgrounds were built on concrete and pebbledashed with broken glass. The rides were dangerous, and kids were routinely trapped, crushed, smashed and bashed by them. You weren’t having a good time unless you’d been hurled from the Witch’s Hat, fell backwards off the swing or skidded, tripped or fell while playing tag and grazed your hands and knees. They were good times. Rides were faster, higher and taller than some houses. Slides were only really fun when you were pushed off, fell off or slid down the wrong way.

According to Google

Louise Jane King

Amy Winehouse is giving it loads in next door’s garden, absolutely belting it out somewhere up there in their Prunus domestica.

Kylie Minogue’s hidden in my leylandii today but I’m not moving again to take more pictures on my phone of their leafy stages.

Not shifting from here. No way. Am loving this luxurious flannel of sunshine cascading across my face, my arms, my toes; smiling light projecting through my eyelids like a cinema, lazing here on cushioned sun-lounger bliss…

No more shivers pulsating my bones. No more twisted hacking coughs. Sweet soft air in, and out, in, and out. Halle-fucking-lujah.

I think that’s Joan Jett next door but one, in whatever tree it is, rocking her shrieks and cries. And behind them all, a choir of unknown artists, a tableau of trills and cheeps and twittering – conflicting keys and beats that somehow work as one.

How have I never noticed them before, these songbirds?

70 Goldfinch Lane

Linda Young

70 Goldfinch Lane lay dormant. The sticky, grimy yellow walls and ceilings just gazed at each other, like some dumb and useless junkie. Nothing stirred. Letters piled up at the front door and spilled like a tidal wave down the hallway: takeaway menus, electric, gas and water bills – first, second and final warnings – birthday and Christmas cards, subscriptions and renewals. None were acknowledged. None were opened.

70 Goldfinch Lane was dead.

*

Georgia had a new regime. For her, lockdown and working from home meant she was allowed one daily walk, and she had now explored several routes. At first, she had struggled to go more than a few blocks, but now, her extended five-kilometre walks took her outwards, beyond the small semi-detached houses and away from the main roads. Her long, blonde ponytail swung back and forth as she strode into her exercise. To the right, past the Duke of York pub on the corner of the busy main road, there lay an interesting lane she had discovered. She’d been aware it was there, of course, but she’d never taken the time to really explore it before. She liked it.

The path on both sides just ran out at the halfway point, so inevitably she ended up walking along the roadside. Not being a creature of habit, she would randomly pick a side to walk on, which meant that sometimes, like today, she walked with her back to the oncoming traffic, cheerfully disregarding common wisdom that you should always walk towards traffic. She smiled. Why did people always assume you were ignorant, when you chose to do something a different way? What was it with the routine that people loved? What asinine lives people must have that they felt compelled to walk on the same side of the pavement every time, always eat at the same time every day, always meet the same type of people, always take holidays to the same place and always live in the same place. Where was the joy, the freedom, the expression? She wanted passion, energy, vibrancy and colour in her life. And new discoveries.

The morning was crisp and sunny. There was still a coolness, but a promise of heat to come. Birds chirped expectantly and she could hear a nearby woodpecker. She loved this road. It made her smile. It was exclusive, but not showy. Smaller properties were dotted between the larger, more rangy dwellings, but even the tiny houses were detached and had character features. This one she was passing now was a low level, pretty, brick and flint bungalow, with an unusual round window in the eaves above the garage. It also sported a grand gravel driveway and an immaculately trim front garden. The front door was sage green: smart, clean and tame. She found herself wondering who lived there – were they clipped and sheared, neat and orderly too?

Continuing her route uphill, she stopped occasionally to let the odd car go by. Being a driver herself, she knew the narrow lane was difficult to navigate; many of the driveways were blind and the track meandered lazily. People often appeared from behind hedges, or hidden gateways or trees. Some speed bumps introduced years ago had thankfully slowed down traffic.

Crossing the lane, she passed 70 Goldfinch Lane, and spotted a laden skip out the front. It blocked the entrance to the house, which was a detached and neglected property, the garden severely overgrown. What bothered her most was not the high grass, the bushy wide shrubs, the leggy-limbed trees nor the weeds growing through the gravel. It bothered her that there was a grey Ford car to the side. It was in reasonable condition, definitely not too old, but it was clearly unused. How could it be? It could not escape the driveway!

This was the second month of lockdown; the eighth week. The clearly empty property disturbed her. Why was the skip never emptied, or collected? It was full to the brim.

*

Georgia shook herself out of her apathy. She’d recently signed up for an online property mentorship course and there was a 7.45am webinar today. Opening her battered laptop, she forced herself to wake up for the early start. Today being Saturday, she would normally lie in. But today, she was ‘property girl’, and she was ‘opening up her eyes to a new and vibrant opportunity’ – according to the Facebook marketing blurb.

Zoom meetings had become a thing. Prior to Covid-19, three quarters of the population would have happily lived without video conferencing, but now, with social distancing, restricted travelling and the two-metre rule, Zoom had become the communal communications software of choice. Her newly installed microphone needed a try-out, so she plugged that in, but she was not sure whether to switch video on, or leave it off. She opted for bravery. This would seem more sociable and friendly when she first met everyone. Wouldn’t it? She clinked the link for the webinar.

Two minutes later, she panicked, left the meeting then hastily re-entered with audio only. No one had been in camera mode, apart from the facilitator and her. She was horrified. Why didn’t people give you protocols prior to joining? How very embarrassing.

Back in the webinar now, she wondered if she had missed something ground-breaking. It seemed unlikely.

So Georgia was surprised when, instead of finding the facilitator still droning on about ground rules and format, she found two women well into a thought-provoking presentation. She pulled her chair nearer, donned her glasses, and leaned forward. The discussion was about creating direct-to-vendor relationships that bypassed estate agents. Wow, this was interesting. Calls to action combined with Do It Now tasks, plus some realistic goal-setting exercises with previous mentees in break-out groups meant she finished the webinar on a high.

Right then, she said to herself, what are you going to do today to get nearer your goal? I’m going to get myself out there. To let people know I’m in the game. So, armed with only pen and paper, she got to work on a letter.

Locky’s Tale

S. Thomson-Hillis

Extracts from the diary of Locryn Endelyon, charting her journey as a Crystal Candidate.

ACY 763: Full Moons 2

Today they took us up to the Crystal Plane for the first time.

Me, Doryty Mensin, Kitty Lalow, Soren Mavyn and Noy.

It wasn’t that impressive. Just a suite of rooms in the tower, at the top of the Keep, with lots of windows, all pale marble, and a smoked-glass cage in the middle. That’s the actual Crystal Throne, the seat of the Great Crystal that powers the Keep. It smelled of lemons – I think it was polish – and was totally underwhelming. They didn’t even open the cage door so all we saw was a bulb of white rock, so tiny I swear it could’ve sat on my palm. Then they made us touch the cage and swear the oath and promise to study our best for the Final Test – yada, yada, yawn.

That’s seven whole years away. Seven. Count them, Mother dear. That’s forever!

While we’re at it, I don’t see why Noy had to come too just because he’s my brother and shows potential. He’s almost three years younger than us and a nuisance; he only took the test because I was babysitting and he’s forward for his age. Hah! Everyone says our family is lucky the genes showed twice in a generation and to look after him because he’s only little. Newsflash, Mother dear, this is the Noy-some brat and eleven isn’t that little. Noy-some as in noisome, as in poisonous-know-it-all brat. So there, Mother dear, so there.

From now on I’m going to write everything down for posterity. I’m not a child; I’m a Crystal Candidate, that means I’m important in my own right, not just because I’m an Endelyon.

Granddad, Assius Endelyon, has been the Link for over ten cycles, and as each cycle is seventy years long that’s seven hundred and sixty-three ACY come next Full Moons 6. He’s seven hundred and seventy-four years old. I knew he was old but that’s awesome. He’s not really Granddad, of course. We only say Granddad out of politeness because we live with him since we lost Father. I asked Mother how long did a Link live, but she said it was all in the Chronicles and what did we learn at school these days? Well, obviously not much history, Mother dear. I can do my maths though. Maths and bioenvironmental zoology. So there, Mother dear.

He took over from Kerry Mavyn when the Troubles ended. We say Troubles and mean war. It was a war. The Crystal brought us here; The Land welcomed us and something happened; nobody, not even the Head Chronicler, knows what. War. Still is. My father’s patrol was the last to explore out there. We stick to the Keep and The Land lets us and that’s life. The Chronicles show seven hundred and seventy colonists led by Yre Endelyon, the first Link and my direct flippety-flop-flop-times-removed uncle, landing here, but don’t say from where. The Chroniclers have written a lot about the beginning, but I think they made up the bits they didn’t understand. It’s marked Verbal Histories. We only started counting time properly after the Troubles, that’s why they call it Adjusted Colony Year and the Colony is yonks older. Assius was the same age as Noy when he became a Link. When you look at the Noy-some brat that is just terrifying. I hope Noy never finds out. There’ll be no holding the little dear.

At Granddad’s tests there were seventy candidates, and today only five. Mother says it’s a worry and what happens if there are no more Links? How will we run the Keep? She worries about everything. She wants the Link Designate to be Endelyon. People rely on Endelyons. Well, this time there are two Endelyons, me and Noy. Mother is that proud I swear she’s going to bust.

Me? I think it’s scary.

It was all a bit sudden, the call for a new Link. Barring accidents, the Crystal keeps the Link alive forever and the rest of us hit seventy if we’re lucky, everybody knows that, Mother dear, so why? Yre Endelyon was over eleven hundred years and murdered by the Candidate Designate at the start of the Troubles. Granddad has yonks left so why. He’s a bit vague, I know, and stays in his rooms, but he’s fine so long as he takes his pills. All he has to do is go up to the Crystal Plane and talk to the Crystal for an hour a day so it makes our power and runs the Keep.

What’s the job prob? I don’t know.

I wonder what it’s like to live so long?

A good or bad thing, Mother dear?

I asked Granddad and he stared into space (he thinks about anything for yonks) and then he said, yes, Locky, it is scary. After that he didn’t say much; I thought he was going to cry. Then he started to ramble on about the depressing lack of genetic material. Then he thought some more and said don’t worry about Noy and he was glad there was a Mavyn, too. He got that look in his eye and droned on about Tess Mavyn for yonks and she’s been dead forever. Mother said if Granddad hadn’t had so many damn soft spots for so many damn women, we wouldn’t be in so much damn trouble now. Three damns in one sentence? Wow! I know I wasn’t meant to catch that rant! Granddad says Soren Mavyn looks like Tess. She must’ve been very pretty because he is such a hottie. Granddad also said to watch out for Noy and sort of smirked.

Well, it’ll only be the five of us for the next seven years, side by side, five by five, class by class – oh Great Crystal, why me? I liked school. You can merge, Mother dear, merge.

Happy Death Day, Hairy Otter

Dave Golder

‘Happy death day to you,’ sang the plump, rosy-cheeked ghost to the tune of ‘Happy Birthday’. ‘Happy death day to you. Happy death day dear…um…’

Her warbling, soprano voice came to a faltering halt.

‘Sorry, what did you say your name was?’ she asked.

Ernest sighed.

‘It’s Professor Ellington,’ whispered Kate from the far side of a library stack, so loud Ernest wondered why she was even bothering to hide.

‘That’s rather long,’ said the singer. ‘Can I call you Ellie?’

‘I’d rather you didn’t,’ said Ernest. ‘But if you must, Ernest will do.’

She recommenced her performance in a trilling, highpitched yodel that would have shattered every glass in the library were she not a ghost. As it was, Ernest found himself envying the still-living patrons of the university library, who milled about amongst the stacks, blissfully unaware of the caterwauling assault he was being forced to endure. The pink velour tracksuit the singing spirit wore did nothing to enhance the experience. People couldn’t choose what they died in (if they could, Ernest would have chosen a less threadbare suit), but as far as he was concerned there was no excuse for ever having worn such a hideous item in the first place.

As the blancmange-coloured ghost belted out the final word of the song – sustaining the ‘Yoooooouuuuuuuuu!’ through what felt like several minutes – Kate emerged through the stack behind which she’d been hiding. She clapped enthusiastically, a broad grin on her face, then looked to Ernest for approval.

‘Well?’ asked Kate.

‘Um, delightful.’

‘You’re sure? You really liked it?’

‘It was… unique.’

The singer, thankfully no longer singing, beamed. ‘I was always regarded as one of the leading lights of the Lower Piddlington Amateur Operatic Society. My Yum-Yum was legendary.’

Ernest could only assume the Lower Piddlington Amateur Operatic Society was desperate for members.

After enduring a few more minutes of bland pleasantries, Ernest was relieved when the would-be opera singer finally departed, claiming to have a busy social diary. Ernest assumed this was so much hot air; no ghost had a busy social life. She was probably just embarrassed at Ernest’s lack of enthusiasm. He did try. He was good at polite, he could handle that. It was part of his mid-twentieth-century, middle-England, middle-class upbringing to avoid hurting anyone’s feelings if at all possible. But equally, it was part of his mid-century, middle-England, middle-class upbringing not to gush excessively. He couldn’t fake sincerity. Even in life he’d been completely see-through.

Kate remained, though. She didn’t seem bothered by his surliness, not now, not ever. Nothing appeared to get under her skin. He put that down to the fact that, in life, she’d been in the WI. As a breed, he found, the WI had emotional hides like rhinos.

‘Happy death day? What kind of madness is “Happy death day”?’

‘It’s a thing.’ Kate grinned. ‘A ghost thing. We all celebrate it.’

‘Well, dear lady, I’ve been dead considerably longer than you, and I can assure it is not “a thing”.’

‘Okay, it’s a Harry Potter thing.’

‘A what thing?’

‘Harry Potter.’

Ernest hoped his blank look would be answer enough.

Kate sighed good-naturedly, like a mother surveying the mess left after a child’s attempts to make scones. ‘I can’t believe you haunt a library and you haven’t heard of Harry Potter.’

Ernest snorted. ‘Madam, I haunt nowhere. I am condemned to live out my afterlife in this library, but I certainly don’t haunt it.’

This was true. Rather, Ernest felt, it was the library that haunted him.

In life he’d been an academic, the kind of old-school professor far happier researching into the most cobwebby corners of scholarly knowledge rather than dealing with a revolving door of students who required tutoring. Books were his real passion. The written word was his lifeblood. While he had, what he would like to think was, an informed appreciation of all forms of classical culture and fine art – painting, opera, theatre – literature was his religion and libraries his place of worship. Foremost amongst which was this vast university library with its labyrinth of ancient, dusty, towering stacks. If only those annoying students could have been kept out, it would have been heaven on Earth.

In death, though, the library was Ernest’s hell. Or, more precisely, his purgatory. He was trapped in an afterlife surrounded by untold millions of books he couldn’t read. Couldn’t even touch. He would reach out a hand and it would pass right through their spines. An Aladdin’s Cave of prose so agonisingly out of reach.

He could look over other people’s shoulders while they were reading, which was some small succour, even though it meant his reading material was no longer ever of his choice. He might fancy some Milton, but have to put up with Melville. (While Ernest admired the American author’s attempts to reveal that it was God, not the devil, in the detail, he could never raise much enthusiasm for all those chapters on the minutiae of whale anatomy.)

‘So what is this Hairy Otter?’ he asked.

Jubilee Summer

Gary Couzens

When they opened the staff training centre a couple of miles outside Greyston, I didn’t want to go there. But I knew I’d have to, sooner or later.

On the way, I drive through the town itself. Although this place where I grew up is much the same as I remember, the roads in the same location, the primary school I went to still there, everything has somehow shifted. It’s the day after the four-day Golden Jubilee holiday weekend, and the buildings seem shut in on themselves, silent, long shadows inching across the playground. I don’t see any children. Maybe it’s the school holidays? I can’t remember. Having no children of your own does that to you.

It’s three in the afternoon. Half a dozen mid-teenage boys cluster around the entrance to the big shopping centre that’s opened recently. When I and my friends were that age, we’d walk along this street, stopping when something in a shop window caught our interest, or to turn our heads as a good-looking boy went past. When we were a bit older, we’d walk along here at a later hour, in our party dresses, thick make-up and too-high heels, on our way to the town’s – then – one nightclub.

I’ve come early. The course I’m attending doesn’t start until tomorrow. I knew I’d need the time.

*

The summer of 1977 was the Summer of Punk as well, but at the age of eleven I wasn’t really old enough to know much of what was going on. My older sister Gemma was the real punk in our family. 1977 was the year I changed from junior school to secondary, and my life changed in so many ways.

That was the summer of Luke, too.

I often wonder what he’d be like if, somehow, I were to meet him again, now. Married perhaps, children maybe, possibly working up to his first divorce, while I’ve stayed determinedly unmarried and childless. Would we have anything in common now, as we had at eleven years old?

*

I check in at the training centre. I’m carrying my overnight bag down the corridor to my room when I hear my name being called: ‘Thea!’

I turn. It’s Jerry, from our Docklands office; we know each other from previous courses. He’s in his early forties, one of those men who combats hair loss with an aggressive number-one crop, but is too jowly and lacking the bone structure to carry off that kind of look. He’s married with teenage children but regards his nights away as licence to play the field. But he’s never tried it on with me, for which I’m grateful. With the unspoken understanding that there’ll never be anything between us, we’re much friendlier towards each other than we could have been.

He walks in step with me down the corridor. ‘Did you see the procession yesterday?’ he says, in his broad East End accent. ‘Wasn’t it bloody marvellous? One in the eye for those people who knock the Royal Family.’

‘I saw bits of it,’ I say. We’ve reached my room. As I unlock it, I say. ‘I was too busy listening to my CD of Never Mind the Bollocks.’’

‘I never would have guessed you’re a punk, Thea.’

‘See you at dinner, Jerry.’ I shut the door behind myself.

*

‘The Sex Pistols? You must be joking! They can’t even play!’ That was my brother Dominic, and it was one of many arguments he had with Gemma. They were only a year apart, had gone to the same schools together, and were forever being compared. Dominic was at University, somewhere Gemma had no intention whatsoever of going herself. She’d just left school that year and was working in Sainsbury’s.

These arguments never really ended, only stopped. Dominic would go into his bedroom and play his Yes albums. We didn’t see much of him anyway: he spent much of his first year’s University vacations at his girlfriend’s up north somewhere. Gemma hadn’t won the argument but hadn’t lost it either: she’d stand there with a little smile breaking out on her face. Dominic simply didn’t get it.

Sometimes, when we were alone in the house that summer, Gemma would hijack the record player and play her punk LPs as loud as she dared. We pogoed around the room, finally collapsing giggling onto the settee. I knew all the words to ‘Anarchy in the UK’ and ‘White Riot’ and ‘New Rose’. There was the occasion when she made me up into a miniature redheaded version of Siouxsie Sioux, to my parents’ horror…but maybe that was a little later. Gemma had a boyfriend, Keith alias Brian Damage, twenty years old and guitarist and lead singer of local band Cum Stains. Their first and only gig, in the back room of Keith’s parents’ house when they were out, was interrupted by the police. His finest hour was walking down Greyston High Street just after the council had passed a byelaw forbidding anyone with non-human-coloured hair from the town centre. He’d dyed his bright orange. He lasted five minutes before he was arrested to a chorus of jeers and catcalls. Needless to say, Mum and Dad didn’t know about Keith, but Gemma spent as much time as she could with him. Once I passed them kissing in public, in Greyston High Street.

I looked up to my sister. She was seven years older than me, but somehow that age gap didn’t matter. She was always protective of me – and still acts that way now – and that helped when we heard the raised voices from behind the closed door of our parents’ bedroom.

Often I would ask my mother if I could go round to Luke’s house, which was two blocks away. I remember Mum with bags under her eyes, or sipping at her pre-dinner sherry. I’d help her in some small way, like laying the table for dinner, and she’d let me lick the dessert spoon. With any luck she’d be in a good enough mood so she’d allow me to do what I asked. I was the youngest, the one who was a surprise, and I played on that.

‘Oh all right,’ she’d say.

Sometimes Luke would spend the evening here, on a Saturday night as we watched Doctor Who followed by The Generation Game and The Duchess of Duke Street. Occasionally it was an informal babysitting operation, and he’d spend most or all of the night on a lilo in my room while his mother went out. Or I’d be in his house until Dad collected me just before my bedtime, and sleepily half-protesting I’d go home.

*

In my room I change out of my clothes and I have a leisurely shower. Tired after a two-hour drive, I lie on the bed and distractedly watch Countdown on the small TV set. After it finishes, I flip through the channels, finding nothing that interests me.

Two hours until dinner. I drink a coffee which reenergises me.

I can’t stay here. I know what I have to do.

Ten minutes later, I’m driving out of the car park, back towards Greyston.

Protest Song

Alice Missions

‘I’m sixty-nine and three quarters.’ Those are words I never thought I’d say. I haven’t counted my age in quarters since I could count my age on my fingers.

But needs must.

I peer over the assistant’s shoulder (Assistant? Not much. Not assisting, hindering more like. A hinderant?). I can see Martin looking back at me from inside the shop. Lips parted, a frown hesitating on his forehead. A puppy that doesn’t yet know what he’s meant to be scared of. I wave him to go on without me, but then immediately question the wisdom of this.

‘Please,’ I say, ‘my husband, he’s inside already, surely you can just let me in, he needs me.’ I don’t add that he hasn’t done a supermarket shop on his own for over thirty years. Such detail would be unpersuasive.

The hinderant simply nods at the Over 70s sign. I study his expression, trying to work out whether his newly acquired authority is a source of pride or terror for him. He’s young. I realise with a jolt that by young I mean under forty. He’s grown up pampered in his equal-rights world, a place where men can cook to impress women, where grocery shopping holds no fear for them. He probably even knows where the bloody mayonnaise is kept. (Those pesky shelves above the frozen veg cabinets. God, Martin would never think to look there!) I wipe a bead of sweat from my forehead before I remember that face-touching is as taboo as smoking now. I quickly look at the ground to avoid the hinderant’s judgement.

If I looked up, I would recognise his face. It’s one of hundreds of faces I normally pass on a Saturday morning, without acknowledgment or second glance, as I trawl up and down the aisles. Happily passing within two metres without thought. Now nothing outside the house is done without thought.

Now the hinderant has been armed with a tabard (some slogan about the NHS hastily printed on it) and a facemask. Fat lot of good those will be to him if this queue turns ugly. For a moment I feel almost gleeful at the prospect of a riot.

And there have been reports of things going ugly. Not many. Just here and there. I read one story about a supermarket manager who had to call the police at closing time. He described the shop like a rowdy pub where the locals had turned on the landlord. (Or it might have been the overzealous journalist that came up with that one.) The manager thought he was going to die. He wasn’t hurt. He is suing his employer for psychological injury.

There are other stories of people smashing supermarket windows to get in. They use trolleys mainly. The newspaper described them as ‘rioters’. There’s a minimum number of people you need for it to be legally classed as a riot, though I can’t recall how many. I chance a glance at the queue behind me. If enough people rammed the windows at the same time…

My eyes dart in the direction of the trolley bay. It’s empty. The trolleys are now inside the store. We’re issued one as we enter, freshly wiped down, of course. They say it is for hygiene reasons.

I sigh. What would I know about rioting? What would I know about anything as far as society is concerned? Perhaps I should feel grateful that this young(ish) man barring my way can even see me. I have been invisible for at least twenty-five years.

I flare my nostrils, inhale deeply, hoping the extra oxygen will give life to the flame that should be rising in my belly. A little fire is all I need. There used to be plenty of fire in there. The kindling is damp; if only I could dry it out enough.

I used to know how to make myself heard. I need that. To make myself heard. To make my point. I can do it. I can be it. Someone who stands their ground, someone who fights their corner.

My mind is suddenly crowded by the lyrics of a dozen protest songs that I thought I’d forgotten. No. I don’t need those now. I push them away, wait for new words.

But when I open my mouth to speak, I’m ashamed to hear a single, pathetic, pleading, ‘Please?’ usher forth.

I can’t even look at the hinderant as he answers me. He doesn’t bother saying, ‘No.’

‘You’ve less than an hour to wait now.’ It’s either sympathy or pity in his voice. I don’t care to dwell on which, both are equally useless to me. He has already turned his attention to the queue behind me. They come forward brandishing their passports and driving licenses a little too smugly.

No one seems to mind that the queue all pass within two metres of me. I am a non-person again and, in an hour, this swarm of locusts will have stripped the shelves all but bare.

The Thing About Seventy features tales of love, loss, lockdown, dragons, abandoned houses, dead people, mystical crystals, rebellions in the supermarket and vanishing numbers. And in all, there’s a thing about seventy. It’s available from Amazon as a paperback (£7.99) and as an ebook (£2.99). For more information about Rushmoor Writers, click here. They’re currently open to new members.