Costanza Casati is a writer and screenwriter. She was born in the US, but grew up in Milan, in Italy. She studied at universities in London and Oxford before graduating from the prestigious Warwick Writing MA with a distinction. Her short stories Rotten Roots, Horrible Feet, and You Asked For It, have all been published on Nothing In the Rulebook and she’s written and produced documentaries for Italian television. Her popular bookstagram page (@youngpeopleread) features interviews with writers from all over the world.

She’s just released her debut novel, The President Show, which is now available to buy from Amazon. Set in a dystopian world, run by a sinister totalitarian regime, the novel follows Iris, a nineteen years old thief. She’s captured and forced to take part in the state-run President Show, a reality programme where ‘Lovers’ have to entertain politicians in a bid to win their freedom. Described as Vox meets The Hunger Games, The President Show is a story of resilience, abuse, betrayal and hope.

Nothing in the Rulebook caught up with Casati just as the book was published. We asked her what the publishing process was like, for the name of the stories that made her start writing, and the advice she has for young writers like her.

INTERVIEWER

Hi Costanza. Could you first tell us a little about yourself? Where do you live? What’s your background/lifestyle?

CASATI

I was born in Texas in 1995. I moved to Italy when I was two and grew up in a small town near Milan – my whole family is Italian. I then moved to London after finishing high school and lived there for five years. I’m currently back to Italy and quarantining here to be close to my family. In addition to writing novels, I’ve been working as a freelance screenwriter and journalist.

INTERVIEWER

Who or what inspires you?

CASATI

Many things inspire me depending on what I’m writing – a beautifully written book, current world events, exceptional figures in history. Writers who inspire me are the ones whose books can make me cry and stay in my mind for a long time after reading them – Margaret Atwood, Madeline Miller, Elena Ferrante, Sally Rooney.

INTERVIEWER

Is writing your first love or do you have another passion?

CASATI

Writing is definitely my first love. I spent my childhood reading and making up stories – I used to draw before I could write. I then started writing stories when I was eleven and I don’t think I’ll ever stop.

INTERVIEWER

Your debut novel, The President Show, will be released on 8th March. What is it about the book that you’re most excited to share with readers?

CASATI

I’m most excited to share my characters with readers. The President Show follows a young woman named Iris as she tries to survive on a reality TV show where she has to entertain powerful politicians. My favourite part of the story is really Iris’s journey from prisoner to defiant heroine, and the bonds she forms and breaks with the other young women on the show.

INTERVIEW

In preparation for the novel, you’ve filmed a lot of conversations with other writers and friends, discussing the themes of the story. What are some of the most interesting things to come out of those conversations?

CASATI

It’s definitely the research that went into those conversations. For a talk on rape culture and headlines about abuse (we were discussing a few cases of rape, including a recent Italian scandal), I discovered an ISTAT survey that proves that 24% of Italians still think women get raped because of the way they dress, while 39.3% think women can avoid rape if they really want to. Another scary statistic came out as we were doing a poll on the obsession of young people with fame and perfection as well as the unrealistic beauty standards on social media. To the question ‘have you ever wanted to change a part of your body you don’t like?’ more than 80% of people voted ‘YES.’ Interesting, but scary stuff. I’d also highly recommend the two documentaries we mentioned in those conversations: Filthy Rich and The Social Dilemma – both available on Netflix.

INTERVIEWER

Tell us a little about your main character, Iris. How did you go about getting into the head of someone in her situation? Did you watch any reality shows as research? What did you learn?

CASATI

Iris is a very resilient heroine. She is strong, resourceful and protective of the people she loves, but she is also very distrustful. She despises The President show and the other contestants, and yet she understands that the only way for her to win the show and go home is to perform and be like them.

I watched some episodes from globally famous reality shows – Love Island, Big Brother, The Apprentice and Survivor – and one of the most interesting things I learnt is the bad message that reality TV sends about human behaviour. Lies, a lack of fairness and compassion, plots to get other players voted off the show are not only accepted on reality TV, but they are rewarded. Most of these shows are about finding weaknesses in the other competitors and throwing them under the bus, and this dangerous mentality of winning at all costs deeply affects our society.

I also researched the stories of victims from famous sex political scandals. Reading testimonies of women like Virginia Roberts Giuffrè – one of the most outspoken survivors of Jeffrey Epstein’s sex trafficking ring – who were groomed and exploited by powerful men was crucial for me in order to write The President Show.

INTERVIEWER

What has the process of publishing the novel yourself been like? The cover, by Sophie Parsons, is fabulous. What was it like, seeing your ideas and characters interpreted by someone else?

CASATI

I love the cover! I came across Sophie’s work on Instagram and contacted her. She loved the idea behind The President Show and worked on a couple of illustrations – one of them then became the cover. Seeing my ideas illustrated by her was a dream come true. I love the sadness and melancholy of Sophie’s illustration – it’s almost as if the two girls on the cover are mirrors, each trapped in her own loneliness.

Working on every step of the publication has been very tough – I’m not going to lie – but also very rewarding. I learnt a lot, and I keep learning, but in the end the feeling of holding your book in your hands for the first time is probably the best.

INTERVIEWER

Which writers should we be paying particular attention to at the moment?

CASATI

This is a great moment for feminist retellings of history. I’ve recently interviewed two authors whose debuts are coming out this year – Annie Garthwaite’s Cecily and Elizabeth Lee’s Cunning Women – and both are books I’d highly recommend. You can watch the interviews on my bookstagram page here.

INTERVIEWER

Can you tell us a little about your creative process? How do you go from blank screen to completed manuscript? Do you plan the plot before you write or do you just dive in?

CASATI

I don’t plan a lot before the first draft. I just dive into it and see where it takes me. Then, when it’s time to edit, I draw a detailed plan chapter by chapter to make sure everything works. I rewrote The President Show so many times I lost count, but in the end the most important part of the creative process for me is to connect to the characters, to make sure I understand them, their fears and hopes and dreams.

INTERVIEWER

Do you feel a sense of responsibility as a writer?

CASATI

I do, but mainly for myself. I always push myself to do better, to write better and I don’t stop until I feel that the story is the best it can be. In terms of responsibility towards the readers, I’d like my book to make them think, or simply show them the world from a perspective different from their own.

INTERVIEWER

What was the first book that made you cry?

CASATI

It was an Italian book called Cuore (Heart in the English translation) – the story of a group of schoolboys, their hardships, hopes and dreams, set during the Italian unification. My mother used to read it to me when I was little. Then the Harry Potters, obviously.

INTERVIEWER

What is the hardest thing about being a writer?

CASATI

It has to be the editing for me, but also the assumption that people often make that anyone can write a book. It’s a wonderful job but it’s very hard; it demands a lot of discipline. That said, I feel incredibly lucky and privileged to be able to write.

INTERVIEWER

Name a fictional character you consider a friend.

CASATI

Hermione Granger and Harry Potter. Also Frances and Bobbi from Conversations with Friends.

INTERVIEWER

Which book deserves more readers?

CASATI

Nothing to Envy by Barbara Demick, which is an incredible non-fiction account of the ordinary lives of people from North Korea. It is drawn from the author’s interviews with extraordinary people who escaped the country’s regime, and it is eye-opening.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any friends that are writers? If so, do you show each other early drafts?

CASATI

I do and I’m so grateful for them! I did my Masters in Writing at the University of Warwick as well as attending the creative writing summer schools at Oxford and Cambridge and I was lucky enough to meet some incredible people there. We still keep in touch and give each other feedback on early drafts.

INTERVIEWER

What’s next for you?

CASATI

My next book is my debut historical novel set in Greece in the age of heroes – a feminist retelling of Clytemnestra, the queen who famously murdered her husband after he came back from the war of Troy.

QUICK FIRE ROUND!

INTERVIEWER

Favourite book?

CASATI

The Handmaid’s Tale and The Song of Achilles.

INTERVIEWER

Saturday night: book or Netflix?

CASATI

Both.

INTERVIEWER

Critically acclaimed or cult classic?

CASATI

Lately, critically acclaimed. I love to pick my next book from prizes such as the Women’s Prize for Fiction, the Booker etc.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any hidden talents?

CASATI

I can sing quite well – and I can do the ‘Cup’ song from Pitch Perfect.

INTERVIEWER

Any embarrassing moments?

CASATI

Too many to pick one…

INTERVIEWER

What’s the best advice you ever received?

CASATI

Write scene by scene.

INTERVIEWER

Any reading pet peeves?

CASATI

Romantic clichés.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a theme song?

CASATI

I don’t actually, though sometimes I write listening to the soundtrack of Game of Thrones!

INTERVIEWER

Your proudest achievement?

CASATI

Writing a book in my second language and getting it published!

INTERVIEWER

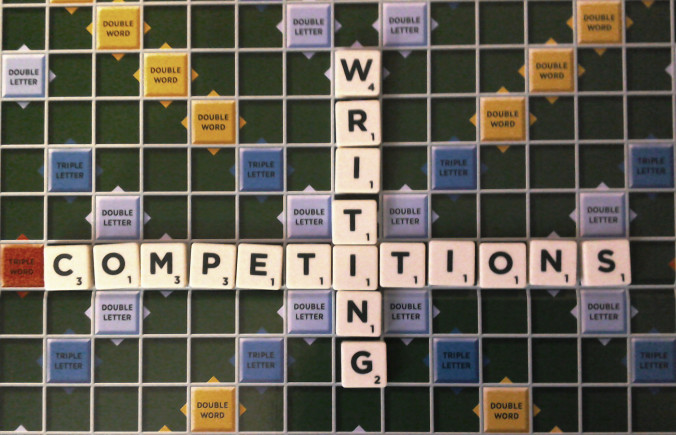

Best advice for writers just starting out?

CASATI

Focus on what you care about – that will make the book special.

The President Show is now available to buy from Amazon. You can find out more about Costanza and her writing on her website. You can also follow her on Instagram and Twitter, and follow her bookstagram page @youngpeopleread.